For every paralyzed person, hundreds or thonds of people could be infected. It is a setback for a plan that should have eradicated the virus from the world a long time ago.

The discovery that polio had partially paralysed a young man in a New York suburb was tiring but also shocking. Tired because it’s the third highly contagious virus to hit the United States in three years, after monkeypox and SARS-CoV-2. Alarmingly, polio has not spread in rich countries for decades, where health facilities, vaccinations and strong public health funding are supposed to keep populations safe. Polio transmission was eliminated in the United States in 1979, throughout the Americas in 1994 and in the United Kingdom in 2003. However, it was there, in the waste water of this young man’s County and a neighboring county, in New York City, as well as in London.

Of course, polio also exists in other parts of the world. Since 1988, a global campaign to eradicate polio has struggled with this daunting task. Last year, the polio virus caused paralysis in two countries that had never been controlled-the disease is incurable or incurable-and has rebounded in 21 other countries.

Disease experts, however, are not surprised by its resurgence in the west. For years, “This should be a wake-up call,” said Heidy Russon, a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and founder of the vaccine confidence project. “We’ve been saying that until we can completely eradicate this disease, we’re all at risk.”

Public health experts consider this an emergency because polio cases represent the tip of the immunology iceberg. For every paralyzed person, at least a few hundred may carry an asymptomatic infection, providing cover for the virus to replicate and spread. It takes time. Sewage treatment results suggest polio may have been circulating in London since February and in New York for at least a few months.

This sense of urgency is why health authorities in London are offering booster doses of the vaccine to all children aged nine or under, that’s why New York City counterparts are urging parents to take their children to get vaccinated — in some New York City postal code, “The first way to prevent polio is to get vaccinated against the polio virus,” said Danyll Pastura, a doctor and associate professor of neuroinvasive diseases at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical School, the vaccine is more than 99 percent effective in preventing polio. “If you are not vaccinated, or your child is not vaccinated against polio, and the polio virus is circulating in your community, you are at risk of developing polio,” said Dr

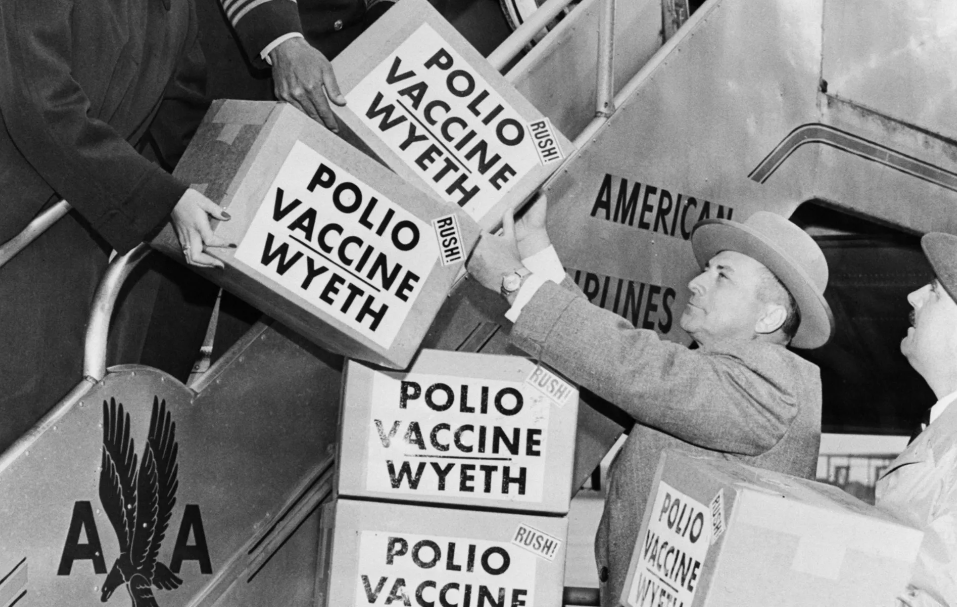

To understand how polio ended in these cities, it’s helpful to look at history. In fact, there are two histories: one about the polio vaccine and the other about how it was used to drive the disease out of the world.

Start with the vaccine formula, or the formula, actually, because there are two formulas. They were born in the mid-20th century in a fierce competition between scientists Jonas Salk and Albert Sabines. Salk’s formula, the first to be approved, is injectable; it uses an inactivated version of the virus that prevents disease, but does not stop the virus from spreading. A few years later, Sabines’s formula used a live, artificially attenuated virus. It does prevent transmission, and because it is a liquid that is sprayed into children’s mouths, it is cheaper to manufacture and easier to spread because it does not require trained medical personnel or careful handling of needles. These characteristics made the Sabines oral vaccine, or OPV, a bulwark against polio and ultimately a major weapon in the global eradication campaign.

Oral vaccines have a unique benefit. Wild-type polio is actually an enterovirus. It targets receptors in the lining of the gut, where it replicates, and then migrates to nerve cells that control muscles. However, because it is in the gut, it can also be passed out of the body through faeces and then spread to other people through contaminated water. Sabines’s vaccine exploits this process. The vaccine virus replicates in children, is excreted, and spreads its protection to unvaccinated neighbors.

Yet this advantage obscures a tragic flaw. Once in every one million doses, the weakened virus reverts to the wild-type neurovirus, destroying these motor neurons and causing polio. The mutation would also make children carrying the retrovirus a potential source of infection rather than protection. This risk is what led rich countries to abandon the oral version. In 1996, when wild polio was no longer present in the United States, the oral vaccine caused about 10 cases of polio. The US switched to an injectable formula, known as IPV, in 2000 and the UK followed suit in 2004.

Polio vaccination requires several doses to produce complete protection, and once protective, children are protected by wild-type and vaccine-derived viruses. As a result, the international vaccination campaign continues to rely on OPV, believing that the risk will diminish as more children are protected. At the start of the process, it was a reasonable gamble that health authorities thought it would take 10 to 12 years to eradicate. However, it is now 34 years since funding shortages, political and religious unrest and the Kervid pandemic, which slowed not only eradication but also the vaccination of all children, and the work is not yet done. Meanwhile, there were 688 cases of so-called“Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus” paralysis in 20 countries last year, compared with six cases of wild-type polio in three countries.

A more complex reason for the emergence of vaccine-derived viruses is the combination of its natural history and the spread of vaccination. There are three strains of poliovirus: Type 1, type 2 and Type 3. Initially, both vaccines contained the three viruses. Over time, as more people developed immunity, the frequency of these strains began to decrease, but not at the same rate. The first to disappear was type 2, so in 2016 planners decided to eliminate the strain from OPV. (because type 2 adheres to the gut more effectively than other types, its addition interferes with the establishment of immunity to other types and makes no sense for a non-circulating strain to dominate the immune response.) In a huge coordinated effort known as“Switching,” The eradication campaign replaced the three vaccines with bivalent vaccines.

But removing type 2 from the formula means that if any type 2 virus reappears worldwide-from environmental repositories, or from people whose systems harbor the mutated vaccine virus-there will be no defense. The bet on the switch did not pay off.

“I think the best way to Johns Hopkins University this is an honest mistake,” said Svea Clother, a medical anthropologist and public health associate professor of polio at the Bloomberg School of Medicine

Most vaccine-derived viruses in circulation today are variant type 2. It mainly occurs in central Africa, where the epidemic has spread across borders. The poliovirus found in New York and London is also a variant of type 2. Importantly, although the two viruses are related to each other and to vaccine-derived viruses found earlier in Israel, there is currently no genomic evidence that they are related to African viruses. They had fewer genetic changes to vaccine viruses than those circulating in Africa, suggesting that they were present for a shorter period of time. They are likely to be imported from places where OPV was used (as in Israel in the 2000s) or continues to be used.

This is important, and not just because these type 2 viruses may have emerged under false optimism. Widely accepted data on the incidence of polio-about one in 200 cases of paralysis-come from studies of type 1. Some data suggest that type 2 numbers are different: there is one case of paralysis for every 2,000 infected people. So if one New Yorker is paralyzed, thonds of people could unwittingly spread the virus. Coupled with community clusters with low vaccination rates, the region may be more vulnerable than is understood.

“It always comes back to immunization coverage,” said John Johan Wertfeyer, director of the epidemiologist and polio eradication branch of the Centers for Disease Control and prevention

It is hard to imagine how society can stop fearing this disease. Some living politicians and celebrities suffered from polio as children. Senate leader Mitch mcconnell, for example, and singer Cioni Mitchell, who suffered a severe relapse in 1995. The polio scare of the 1950s closed schools and theaters and emptied swimming pools, “We need to vaccinate everyone,” said Howard Forman, a doctor and health policy expert and professor of Yale School of Medicine, this was widely accepted at the time; People line up in the streets to get vaccinated against polio and measles-mumps-rubella. “Over time, I think people’s memories fade. I don’t think most people know what polio is now.”

If there is any benefit to this emergency, it may be that it has re-entered the consciousness of people in rich countries of the continuing threat and unpredictable risk of polio. This can only be a good thing for the international campaign to eradicate the disease. The campaign was launched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and one million volunteers from the Rotary International. Since last year, it has been introducing a reworked OPV that targets only type 2 and is unlikely to cause mutations. Even with these sponsors, however, the campaign has been chronically underfunded. New Knowledge may change this.

“The London and New York test results have raised concerns about polio and VDPVs,” said Carroll Pandak, director of epidemiologist and global health experts for the rotary polio booster program, who also stressed the urgency of stopping wild polio and vaccine-derived polio as more people now know that VDPVs can cause paralysis like wild polio. They are a stark reminder that as long as polio exists anywhere, it is a threat anywhere.